Recently released 1973 recordings show that President Nixon privately admitted cannabis was “not particularly dangerous,” despite him launching the War on Drugs and supporting harsh criminalization including its classification as a Schedule I substance. Nixon ignored the recommendation to decriminalize cannabis and used drug policies to politically target the anti-war left and Black communities.

Recently Leaked Recordings Reveal Nixon Considered Cannabis “Not Particularly Dangerous”

In recently released audio recordings from March 1973, revealed by The New York Times, former President Richard Nixon privately admitted that cannabis was “not particularly dangerous,” a stark contrast to his public stance as the initiator of the War on Drugs.

For more news like this, along with all the latest in legalization, research, and lifestyle, download our free cannabis news app.

Nixon On Cannabis: A Surprising Admission

During a 1973 White House meeting, Nixon expressed his lack of knowledge about cannabis while acknowledging that it was “not particularly dangerous.” He also noted that many young people supported its legalization. However, he was unwilling to publicly endorse this sentiment, stating, “It’s not the right signal at this time.”

This admission is significant given Nixon’s role in launching the War on Drugs in 1971, during which he declared drug addiction “public enemy number one.”

Despite his firm public position, his private conversations suggest Nixon questioned the extreme punishments for cannabis-related offenses. For example, Nixon expressed disbelief about a 30-year sentence he had heard of, calling it “ridiculous” and asserting that penalties should be “proportionate to the crime.”

Despite his doubts about the severity of punishments, Nixon played a key role in shaping the federal government’s approach to cannabis. His administration classified cannabis as a Schedule I substance under the Controlled Substances Act, alongside drugs like heroin and LSD, typically indicating a high potential for abuse and no recognized medical value.

Nixon Laid Groundwork for Mass Incarceration

This classification laid the groundwork for mass incarceration, disproportionately affecting Black Americans, who are 3.6 times more likely to be arrested for cannabis possession than their white counterparts, according to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

The Nixon decision also stifled cannabis research. For decades, scientists faced significant obstacles in studying its effects, limiting medical advances. These long-term consequences highlight the disparity between Nixon’s private beliefs and the policies he implemented.

The Shafer Commission Report

Nixon’s private admission that cannabis was not particularly dangerous sharply contrasts with the actions of his administration.

In 1972, Nixon rejected the recommendations of the Shafer Commission, a federal group he had appointed to evaluate cannabis laws. The commission’s conclusions were clear: while cannabis use posed some health risks, criminalization was both excessive and unnecessary.

The report stated that personal possession and occasional distribution of small amounts of cannabis should not be criminal offenses. It also emphasized the need for a significant shift in societal attitudes toward drug use, suggesting that harsh law enforcement was not an appropriate response to cannabis consumption.

Despite this comprehensive analysis, Nixon ignored the commission’s findings and continued to advocate for strict drug legislation. The Shafer Commission Report is now considered a missed opportunity for cannabis reform, especially as its conclusions align with modern arguments for the decriminalization and legalization of cannabis.

Nixon’s Political Motivations Behind Criminalization

A particularly controversial aspect of Nixon’s drug policy is its political motivation.

In a 1994 interview, John Ehrlichman, Nixon’s domestic policy adviser, revealed that the administration’s aggressive stance on drugs was partly aimed at weakening political opponents. Ehrlichman admitted that the criminalization of drugs, particularly cannabis and heroin, allowed the administration to target the anti-war left and Black communities.

By associating hippies with marijuana and Black people with heroin, the Nixon administration sought to disrupt these groups by arresting their leaders, raiding their homes, and portraying them negatively in the media, turning prohibition into a tool of population control rather than protection.

“Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did,” Ehrlichman said in the interview, exposing the cynicism behind the War on Drugs.

—

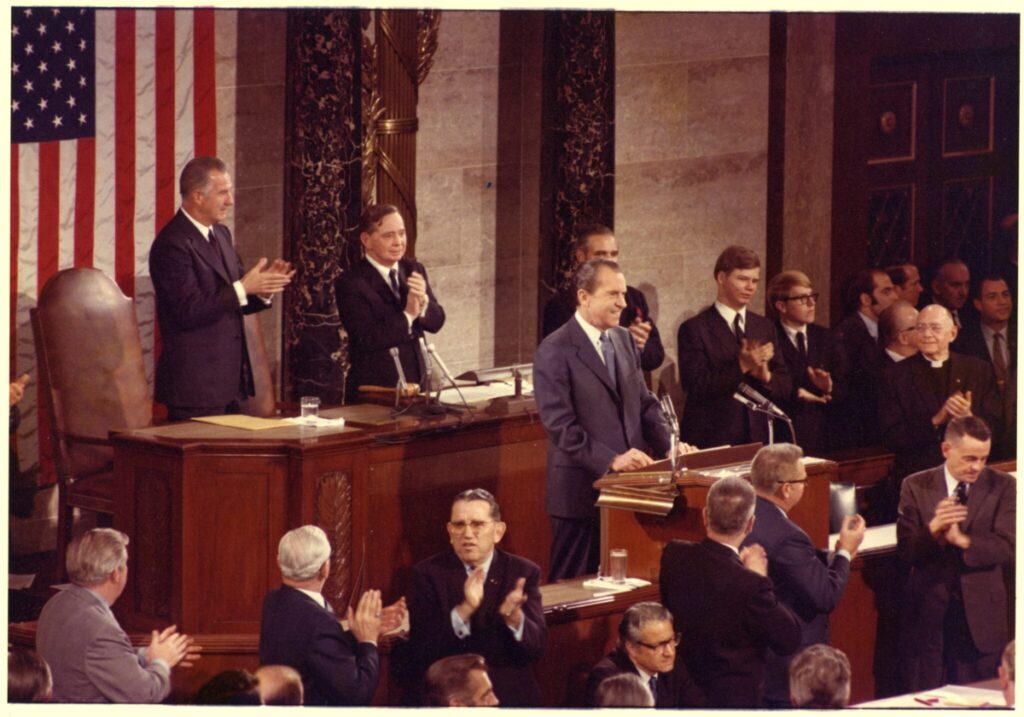

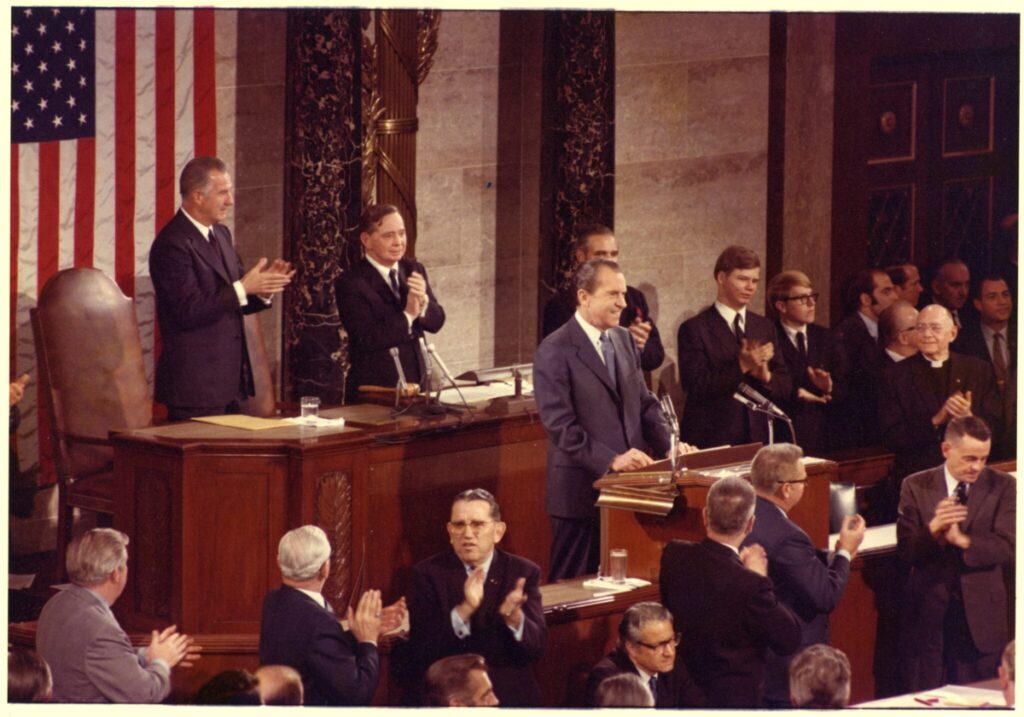

(Featured image by the Whitehouse Photo Office via the U.S. National Archives Catalog)

DISCLAIMER: This article was written by a third-party contributor and does not reflect the opinion of Hemp.im, its management, staff, or its associates. Please review our disclaimer for more information.

This article may include forward-looking statements. These forward-looking statements generally are identified by the words “believe,” “project,” “estimate,” “become,” “plan,” “will,” and similar expressions. These forward-looking statements involve known and unknown risks as well as uncertainties, including those discussed in the following cautionary statements and elsewhere in this article and on this site. Although the company may believe that its expectations are based on reasonable assumptions, the actual results that the company may achieve may differ materially from any forward-looking statements, which reflect the opinions of the management of the company only as of the date hereof. Additionally, please make sure to read these important disclosures.

First published in Newsweed, a third-party contributor translated and adapted the article from the original. In case of discrepancy, the original will prevail.

Although we made reasonable efforts to provide accurate translations, some parts may be incorrect. Hemp.im assumes no responsibility for errors, omissions or ambiguities in the translations provided on this website. Any person or entity relying on translated content does so at their own risk. Hemp.im is not responsible for losses caused by such reliance on the accuracy or reliability of translated information. If you wish to report an error or inaccuracy in the translation, we encourage you to contact us.

Comments are closed for this post.